By Evan Wilt

(WNS)–Teen pregnancy has declined by 51 percent since peaking in the early 1990s, but new government data show more young girls are relying on the morning-after pill.

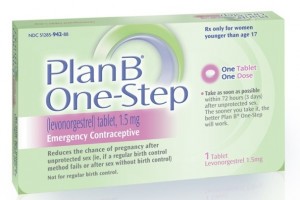

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 22 percent of sexually active teenagers used the Plan B pill at least once. A decade ago, less than one in 12 girls had used emergency contraception.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 22 percent of sexually active teenagers used the Plan B pill at least once. A decade ago, less than one in 12 girls had used emergency contraception.

The popularity of emergency contraceptives is likely due to increased availability. Since 2006, girls 18 and older can buy the morning-after pill without a prescription. But the increasing use of emergency contraceptives also shows the impact of narrowly focused sex education, according to Valerie Huber, president and CEO of the National Abstinence Education Association.

“We have reduced the message for teens that sex plus contraception is okay,” Huber said. “They are only looking at the physical consequences. … It’s better for teens to not have sex.”

The CDC report showed condoms are still the most popular contraceptive; 97 percent of sexually active females used them at least once. Fifty-four percent of teen girls reported using birth control pills.

The new CDC data comes from interviews of 2,000 teens, ages 15-19, from 2011 to 2013.

“Teenagers tend to have sex sporadically. And many of them are therefore not prepared to use contraception,” said Bill Albert from the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. He said a teenage girl is less likely to take a birth control pill everyday if she doesn’t know the next time she will have sex. “So I think that’s where you see emergency contraception playing a role.”

Younger women tend to buy emergency contraceptives most often. The most recent data from the CDC said 23 percent of women ages 20-24 have used Plan B. From 2006 to 2010, only 5 percent of women ages 30-44 reported using the morning-after pill.

In 2013, emergency contraceptives became available to girls under the age of 18. Now anyone can buy Plan B without identification for $35 to $50.

James Trussell, the senior research demographer at the Office of Population Research at Princeton University, said increased access to the morning-after pill probably did not cause the decrease in the unintended pregnancy rate.

He said in the early 1990s, the hope for emergency contraceptives was that they would reduce the rate of unwanted pregnancies and abortions by half. Now, 20 years later, “15 studies have examined the impact of increased access to [emergency contraceptives] on pregnancy and abortion rates. Only one has shown any benefit,” Trussell said.