By Mark Ellis

Beatings by his father put him in the hospital at a young age. “State-raised,” he was incarcerated intermittently from the seventh grade onward, until he reached the most dreaded cellblock at San Quentin.

Beatings by his father put him in the hospital at a young age. “State-raised,” he was incarcerated intermittently from the seventh grade onward, until he reached the most dreaded cellblock at San Quentin.

“My father was a very bitter, angry man, especially when he was drinking,” says Ed Welch, who is currently struggling with a diagnosis of terminal cancer at age 65. Ed’s truck-driver father was a loyal member of the Teamsters, and even became chairman of Jimmy Hoffa’s fundraising committee when Hoffa faced imprisonment.

Welch got into his first fight with dad at age 10, in an attempt to defend his mother. “He nearly knocked me out, and from that point on we had a different relationship. I hated him because of what he did to mom.”

In fourth grade, Welch was kicked out of school for fighting. A year later he was arrested. By seventh grade he was in juvenile hall, which began a journey in and out of the prison system for many years.

“My father was turning me into himself, which I didn’t realize at the time. He turned me into a very bitter, angry person.” Welch says his mother never left her husband because she believed that “any father is better than no father.”

Nominal Catholics, the family went to mass on Christmas and Easter, but Welch says there was really no connection with God.

At 14, a girl he liked invited him to a Billy Graham crusade at the L.A. Coliseum. Graham’s message that day was directed at people without fathers or “bad fathers,” and Graham highlighted the Heavenly Father’s unconditional love for us.

“I never cried and I was in tears,” Welch recalls. He went down to the field and prayed a prayer, but he was not ready to make Jesus the Lord of his life. There was no follow-up or grounding in Scripture. It was a huge missed opportunity.

Family tragedy

Shortly after that, he took his mother’s new Corvair automobile for a joyride with friends while she slept. “I went over a bump too fast with a carload of kids and busted the engine block,” he recounts. “I ran away from home because I knew the trouble I would get for that.”

Arrested at a party, Welch went back to juvenile hall for the second time. While he was there, a traumatic family tragedy occurred.

On the day his mother retrieved her car from the auto body repair shop, she was in a horrifying car accident. “Every bone in her face was broken because of a design flaw in the Corvair,” Welch says. “The steering wheel came up like a projectile and hit her in the face. The car crumpled-up and also mangled her legs.”

When Ed went to the hospital with his father she refused to acknowledge her son’s presence. It may have been due to her poor eyesight or the fact that she was heavily medicated, but tragically, she passed away a few days later. “For years I thought she was mad and rejected me,” he laments.

In anger, he shook his fist at God because of his mother’s untimely death and he continued on his wayward path of rebellion.

When Welch was released from juvenile hall, the courts declined to send him back to his father. Instead, he went to live in a Mormon-run boys home in a rough area of downtown L.A.

To survive in the neighborhood, he joined a Mexican gang and had his first introduction to drugs. After he was kicked out of the Mormon-run home and later a boys ranch, he went back to live with his father.

“I came home like a stranger,” he recalls. “It wasn’t long before we were in a few fist fights, but I was a lot tougher. I knocked him out and he was in a coma for three days.”

Later in life, Welch discovered his father had been abusing his two sisters, physically and sexually. One of his sisters  became a heroin addict and the other developed mental illness. “She became very withdrawn. She lived as a hermit, living in a trailer,” he says. She died alone and no one discovered her mummified remains until weeks after her passing.

became a heroin addict and the other developed mental illness. “She became very withdrawn. She lived as a hermit, living in a trailer,” he says. She died alone and no one discovered her mummified remains until weeks after her passing.

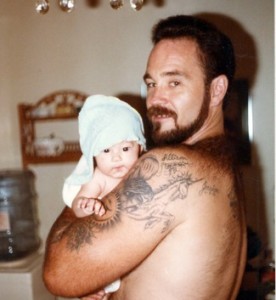

At 16, Welch was arrested for marijuana possession and sent to the California Youth Authority. After his one-year term ended, he met his first love, a 16-year-old girl with a baby. “I fell in love with the baby first,” he says.

He started working in his first real job after his release, but he also was dealing drugs on the side and had joined The Lynchmen, a gang in the San Fernando Valley.

He was asked to enforce some rough justice against a rival gang and stabbed a member of the other gang 11 times. “I hit him in every vital organ except his heart,” Welch says.

Miraculously, the young man survived the attack, but Welch was arrested once more and faced a charge of attempted murder.

After he went back to the Youth Authority, his girlfriend got into drugs and heavy partying. Her baby was taken away by state authorities.

“When I got out of Youth Authority, I was living a criminal lifestyle, dealing heroin.” As an adult, Welch’s next arrest and conviction for selling heroin sent him to San Quentin, his first time in state prison.

San Quentin

It was a dark chapter in San Quentin’s history. “We had more stabbings and killings in one year (1973) than any other year in the prison’s history,” he recounts. His cellblock became known as “Vietnam,” due to its war-like conditions.

In the midst of this spiritual darkness, Welch had his first encounter with God’s Word. “The only thing I could find to read in the prison library was “The Late Great Planet Earth,” he recalls. He had heard about Hal Lindsey’s bestseller, and because of the upheaval in American life with the Vietnam War and other social maladies, Welch became convinced after reading the book that the return of Christ would happen in his lifetime.

After he read Lindsey’s book, he picked up “Good News for Modern Man,” a contemporary paraphrase of the New Testament. God’s Word began to stir his soul and a battle ensued for his heart and mind. “I thought I was crazy. I didn’t even believe in God. I had always been a loser. I thought that if the End Times happen, I’ll probably be on the losing side.”

His brush with God’s Word represented another missed opportunity, but seeds were planted, and improbably, the Hound of Heaven was tracking someone many people would consider “beyond redemption.”

Welch got into weight lifting in prison. After his release five years later, he had 20-inch arms and could bench press 440 pounds. “After my release I was at my pinnacle of violence,” he recalls. He went to work for a heroin kingpin as an enforcer.

“I would go out and collect debts and I had to make an example,” he says. “I would be pretty brutal. I borrowed my boss’s gun once and when I brought it back a guy’s moustache was in the breach of the gun.”

Only five months later he was back in prison after he got involved in a jewelry heist near Universal Studios. At Soledad Prison, he became the “white representative” in the prison yard. “I was there until they had race riots and I became a target for the Crips,” a primarily African-American street gang that had emerged a few years earlier.

A new chapter unfolds

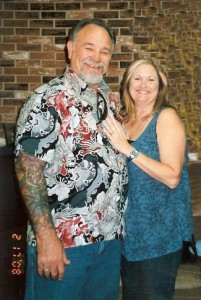

During his next stint at Tehachapi Prison, he met his future wife, Allison, when she visited her brother, one of the other inmates. “She took a shine to me,” Welch says, “and when I got out she was waiting at the gate.”

Allison worked at Northrup Aircraft in the personnel department. When he went over to pick her up from work one day, Allison’s boss saw Ed and inquired about him. “I hadn’t looked for work. I had long hair and was covered with prison tattoos,” he says.

Through a remarkable set of circumstances, Welch was hired and entered a training program set up for minorities. “At 31, I was smart enough to realize this was my big chance to do something good with my life. To become a journeyman usually takes seven years. I did it in three.”

While at Northrup, he built the master tooling for the special door used by the president on Air Force One. He also worked on the F-18, the F-20, and the Stealth bomber.

“I was doing good in a worldly sense, buying new cars and Harleys and partying it up,” he recalls. But he was also unsettled because his sister and niece were not doing well due to his sister’s drug addiction. Welch blamed himself because he introduced his sister to the drug dealer who got her hooked. When his nine-year-old niece ended up on the streets panhandling for food, it shocked him into a time of sober-minded reflection.

Then he learned Allison was pregnant, another jolt to his freewheeling sensibilities. “Maybe we should start going to church,” he suggested to her, but neither one of them had the faintest idea where to go.

Meanwhile, there was a small rental house in the back of their property occupied by a Christian couple and their infant. Unbeknownst to Ed and Allison, they had been praying for their landlords, even though they barely knew them.

Broken appliance

“One day her dryer broke down and she had a washer full of wet diapers,” Welch recounts. The young Christian woman came over, knocked on the door, and asked if she could borrow the dryer.

“I see you often leave on Sunday mornings,” Allison said. “Do you go to church?”

“Yes…why?” the young Christian woman replied, with a shocked expression on her face. She and her husband had witnessed the Welch’s late night, raucous biker parties in their adjoining yard. “Me and my husband were talking about going, but we don’t know where to go.”

Remarkably, a broken dryer full of wet diapers was God’s instrument to lead Ed and Allison to church, where they surrendered their lives to Jesus Christ and began to follow Him wholeheartedly for the first time.

Many years later, Ed became an ordained pastor and a prison chaplain. The first prison he served in was at

Chino, but he also has made many trips to San Quentin to minister the Gospel to desperate men – men as lost and seemingly “beyond redemption” as he had once been.

When Billy Graham came to Los Angeles in 2006, Ed Welch headed the prison ministry outreach associated with the event. “We broke a 50-year record,” he exults, as they visited 30 prisons and jails in Southern California and conducted 70 outreaches to 5,000 prisoners.

Welch discovered he had cancer on the day Pastor Chuck Smith died. “I would like to go out like him, running the race to the end,” he says. In reflecting on his transformed life, he can only say, “God does amazing things.”