By Brian Koonce

KANSAS CITY (BP) – Most preachers wouldn’t dare to tackle writing a sermon and a hymn for their congregation, but that was par for the course for Pastor John and his peers. On New Year’s 1773, he was preaching through 1 Chronicles 17, expositing God’s promise to David.

“Who am I, Lord God, and what is my family, that you have brought me this far?” David asks in his prayer. “And as if this were not enough in your sight, my God, you have spoken about the future of the house of your servant. You, Lord God, have looked on me as though I were the most exalted of men. What more can David say to you for honoring your servant? For you know your servant, Lord. For the sake of your servant and according to your will, you have done this great thing and made known all these great promises.”

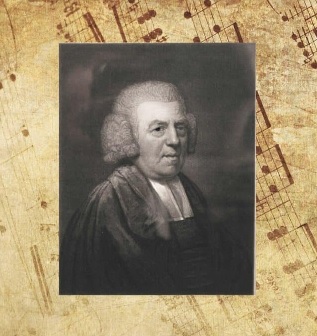

David and Pastor John both were overwhelmed by God’s grace. Amazing grace, even. And so David’s prayer in the hands of a slave trader-turned-pastor named John Newton became the lyrics to one of the most sung hymns – or songs of any sort – ever. “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me.” The seeds for each verse are in 1 Chronicles 17 for those who read closely.

‘How sweet the sound’

2023 marks the 250th anniversary of the hymn, a song synonymous with Christian victory in the face of dangers, toils and snares, as well as man’s overwhelming sin.

“‘Amazing Grace’ is a timeless hymn,” said Matt Swain, the assistant dean of Worship Ministries at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (MBTS). “It spans the ages and it had spoken to generations and people from all different walks of life. Even people who are not Christians or religious at all know the tune and the text to ‘Amazing Grace.’ What’s interesting is that even though everybody just seems to know it, they don’t necessarily quite understand what it is that the hymn is really about, which is somewhat ironic.”

‘I once was lost’

There can be no doubt that Newton knew of what he preached and wrote. In his youth, he famously took to the sea and was heavily involved in the slave trade. He neglected his faith and mocked God and those who believed. As if that wasn’t bad enough, he had a bad reputation… among slave traders. He was a foul-mouthed, insubordinate wretch, even to the point of being imprisoned while at sea, chained alongside the slaves he was transporting. It would take amazing grace, indeed, to save him.

In March 1748, while his ship was tossed by a violent storm in the North Atlantic, a crew member who was standing where Newton had been moments before was swept overboard. He and his crewmates labored for hours to pump water from the ship, and expecting to be capsized at any moment.

The ship did not sink, and two weeks later when it limped into the harbor, Newton began to ponder the mercy he’d been shown. Was he worthy of God’s mercy? Was he redeemable?

‘But now I’m found’

His conversion was not immediate then and there, but the seed of the gospel was taking root and making his need for forgiveness impossible to ignore. “I was greatly deficient in many respects,” he wrote. “I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards.”

He continued sailing in the slave trade between Africa and the New World, but he also got married and soon found himself physically unable and unwilling to meet the demands of life on the open seas. Returning to the teachings of childhood, he began to teach himself Latin, Greek and theology. He and his wife, Mary, threw themselves in the church community, and by 1764 he was offered a pastoral role in Olney, a village of about 2,500 people about 50 miles north of London. It was there he began preaching and presenting poems and songs to reinforce the message of his sermons. A few years later, “Amazing Grace” was born.

“This song really came out of a life of hopelessness, Matt Swain said. “As a sinner – as a wretch – he was radically saved and started a life of ministry and servitude unto the Lord by grace.

“This is just conjecture on my part,” Matt said, “but I don’t know how he could not have been impacted when he looked back on his life, much like David, by seeing the miraculous things that God has done. In some ways it’s testimonial, but I don’t know that it was overtly meant to be testimonial so much as it’s just how grace works in the life of the believer. But you can’t just read through the hymn and know his story and not think, ‘Wow, he had to have had that on his mind.”

‘Grace will lead me Home’

But Newton was more than just a redeemed hymn writer with a dark past. A few years after “Amazing Grace,” in 1779, he moved to London where he continued preaching. He was one of only two evangelical Anglican priests in the capital, and he grew in popularity, even among the Methodists and Baptists of the time.

It was during this time he connected with William Wilberforce, a young member of Parliament who was struggling with staying in office while seeing evil in the world such as slavery. When he sought Newton’s advice, he advised him to “serve God where he was.” Wilberforce followed his advice, and his political views were informed by his faith and by his desire to promote Christianity and Christian ethics in private and public. That included a vocal and active fight for the abolition of slavery, one that Newton joined.

“In many ways, John Newton was kind of like the Billy Graham of his day,” said Angela Swain, associate professor of music at MBTS. “If you think of how Billy Graham was to many of our presidents, that’s how John Newton was to William Wilberforce.”

Three decades after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton published a pamphlet called, “Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade,” describing the horrific conditions of the slave ships during his service as crew. The confession and apology, he wrote, “will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.”

Thanks in part to both men, the Slave Trade Act of 1807 brought British involvement in slavery to an end. While the end of slavery in the New World was still decades away, “Amazing Grace” and its gospel message were taking hold in Britain.

‘No less days to sing God’s praise’

As profound and simple as it is, Newton’s song didn’t exactly catch on at home, and Newton was ready the next week to write a new song.

“It only became popular later in the United States,” Angela said. “Irony of ironies.” It caught on in the U.S. in part due to its musicality and folk-melody, but largely, the Swains believe, due to its message during the Second Great Awakening. “Theology leads to our doxology,” Angela said.

“It’s so plainly a song about the gospel,” Matt continued. “Whether we were saved from something like the slave trade, or if our conversion was less notable than John Newton’s, it still speaks of the power of God unto salvation. For those that experience that grace, we are being brought from death to life, and that in and of itself is a radical thing.”

That popularity lives on, even two and half centuries later. “Lots of people embrace the hymn,” Matt said. “I mean, Elvis Presley sang it.” But beyond the music and at its foundation, “Amazing Grace” is still about the gospel, and that’s potentially what has made the hymn stick around in the cultural consciousness.

“Strong hymns have strong theology,” Matt said. “It’s the grace we’ve been given that gives it that power for those of us who have been saved through the blood of Christ. It’s an even more powerful testimony to know the life of John Newton, to see what the gospel can do in his life of sin.”