The Harvard Professor who confidently proclaimed to the world she possessed evidence that suggested Jesus may have had a wife has now been outed as a second-rate academic who allowed herself to be duped by a con man.

By Thomas D. Williams, Ph.D.

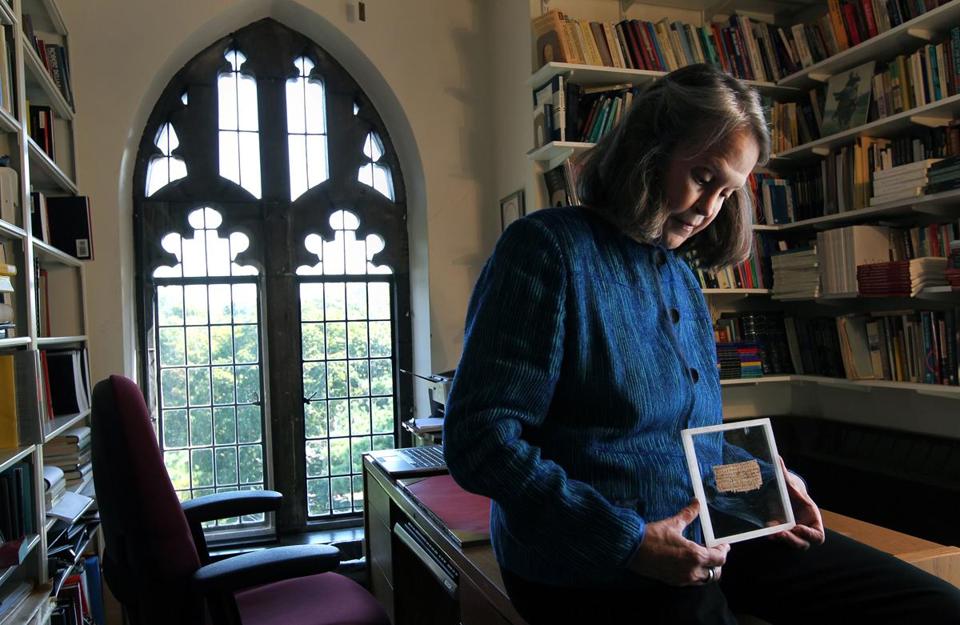

Dr. Karen L. King, professor at Harvard Divinity School, earned her 15 minutes of fame by staking her reputation as a historian of early Christianity on the authenticity of an ancient papyrus stating: “Jesus said to them, My wife… she is able to be my disciple.”

At a splashy roll-out a stone’s throw from the Vatican in 2012, King presented a paper to more than 300 scholars from 27 countries, where she announced the discovery of an ancient scrap of papyrus in which Jesus refers to his “wife,” whom King said is probably Mary Magdalene.

“All of the evidence points to it being ancient,” King later said. “As historians, the question then becomes, what does it mean?”

The Harvard Theological Review published an entire journal edition on the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife,” and the Smithsonian Channel produced a major documentary on the topic. National Geographic confidently announced, “No Forgery Evidence Seen in ‘Gospel of Jesus’s Wife’ Papyrus” in its issue from April 11, 2014.

The problem was, the document is a fake. Dr. King had actually received the papyrus from a pornographer named Walter Fritz, who invented a story of how he had come into possession of the fragment. Described by people who knew him as “an eel,” Fritz told King that he had obtained the text from a colleague who had acquired it in Potsdam in 1963.

King was so excited with the possibilities of the find, however, that she never bothered to check up on Fritz’s credentials or the numerous inconsistencies in his story.

In two separate summer issues, the Atlantic Magazine—which in 2014 had called the findings of Dr. Karen King a “bombshell”—revealed the provenance of the papyrus, undermining the fawning attention that the scientific community showered on the discovery.

The journalist who uncovered the “whopping fraud” was Ariel Sabar, who pursued the origins of the fragment, leading him to the home of Walter Fritz on Florida’s southern Gulf Coast. Despite Dr. King’s unwillingness to reveal the name of the person who had furnished her with the papyrus, after painstaking sleuthing, Sabar found him anyway.

In 2003, Fritz had created a series of pornographic sites showcasing his wife having sex with other men, whom he also claimed had gifts of clairvoyance, prophecy and spiritual channeling. At times, Fritz’s wife would reportedly babble during sex in a language that Fritz assumed was Aramaic, the language of Jesus.

Fritz also had a background in the Coptic language and had previously worked as a tour guide in Berlin’s Egyptian Museum. Moreover, Sabar discovered, just prior to Dr. King’s public announcement of the papyrus, Fritz had purchased the domain name gospelofjesuswife.com.

Fritz also had a background in the Coptic language and had previously worked as a tour guide in Berlin’s Egyptian Museum. Moreover, Sabar discovered, just prior to Dr. King’s public announcement of the papyrus, Fritz had purchased the domain name gospelofjesuswife.com.

When Sabar alerted Dr. King of his discovery prior to publishing his first piece, she said she wasn’t interested and would read the piece when it was published. “I haven’t engaged the provenance questions at all,” she told him.

Sabar later accused King of shoddy scholarship, suggesting that what she called a “lack of information” was really just a “lack of investigation.”

In his later piece, Sabar noted that King was particularly interested in Gnostic texts that assign Mary Magdalene a prominent role as Jesus’s confidante and disciple, since proof that some early Christians also saw Mary Magdalene as Jesus’s wife “would be a rebuke to Church patriarchs.” Her ideological agenda, in other words, disposed her to believe Fritz’s account of the papyrus.

Harvard classicist Christopher Jones had already observed that a forger may have identified King as a “mark” because of her feminist scholarship. The tale does not end here, however.

When Sabar confronted Fritz with his trail of lies and deceit, Fritz admitted the fraud, but then tried to hustle Sabar as well, proposing co-authorship of a new book on the Mary Magdalene angle of Jesus’ life and the “suppression of the female element” in the Church.

Sabar would do the writing and Fritz would do the leg work on the details of the story. Fritz assured him the book would make a “million dollars in the first month or so.”

“The facts alone, they don’t really matter. What matters is entertainment,” he told Sabar. “You have to make a lot of stuff up,” he said. “You cannot just present facts.”