By Moses Wasamu

(WNS)–Before she knew how to read and write, 50-year old Pastor Esther Naitobwagi had to ask someone to read the Bible for her. She had to ask for directions when she visited the city of Nairobi from her rural home in Kenya, and she even asked friends to read text messages on her cellphone.

These days, Naitobwagi can read and write in Kiswahili, Kenya’s national language, and Kimaasai, her native language. She’s one of hundreds enrolled in adult literacy classes offered by the Bible Society of Kenya (BSK) for people in marginalized communities.

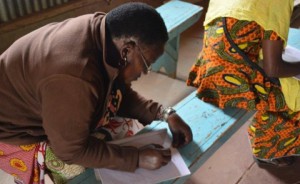

The effort is part of the group’s goal not only to translate the Scriptures, but also to help make sure people can read them. Instructors hold classes in local churches and teach reading, writing, and math skills to adults who often never had access to a basic education.

The effort is part of the group’s goal not only to translate the Scriptures, but also to help make sure people can read them. Instructors hold classes in local churches and teach reading, writing, and math skills to adults who often never had access to a basic education.

Naitobwagi was born into a large polygamous family of close to 40 children. Just a few of her siblings managed to go to school because education was not a priority to her father. Today, she says she is more confident as a preacher in her church.

“When I go out for evangelism, I am able to read my own Bible without asking anyone to read for me,” she said.

But the process wasn’t easy. Sometimes, Naitobwagi had to miss classes to look after her family’s cows. Many times, a grandchild tended the cows in her place. Her husband was always busy with other family responsibilities, she said.

The Bible society offers classes in four marginalized areas in Kenya: Kajiado, Turkana, Pokot and Teso. The literacy classes complement another program called Faith Comes by Hearing, which uses audio Bibles to help people listen to the Word of God.

When adult learners graduate after three years of study, instructors present them with a Bible they can comfortably read.

Program coordinator Benson Njuguna said many churches have requested the program, but lack of funds hinders the group from reaching every location.

Sixty-seven year old Jeremiah Pardiyio is a retired teacher who helps to run the adult learners’ class in Ilbissil, some 40 miles from Nairobi in Maasailand.

The Maasai people occupy a huge area in the southern part of Kenya. In the Maasai districts of Kajiado and Narok, the literacy levels are 30.2 percent and 33.4 percent. Non-readers include pastors, like Naitobwagi, who head churches but have never had pastoral training.

Pardiyio has a class of 30 students with 15 men and 15 women. They learn how to read and write English, Kiswahili, and Maasai, and they also learn mathematics and health education.

The society provides teaching and learning materials and gives a stipend to the adult education teachers. The Kenyan government provides some books and sets the examinations.

But despite the successes, the program faces complicated challenges like drought, pastoralism and migration, and cultural obstacles—some men are uncomfortable sharing classes with women.

On the Thursday I visited Pardiyio’s class at the Full Gospel Church of Kenya, the men came earlier than the women, who trudged in much later. Pardiyio said the women have family responsibilities they must fulfill first before they come to class.

Pardiyio has been an adult educator since 2002. He says the high level of illiteracy among the Maasai stems from girls marrying early and parents not allowing their boys to go to school. Instead, the boys look after their parents’ cattle.

The Maasai keeps large herds of cattle; some have as many as 2,000 cows. In times of drought, they traverse thousands of miles between Kenya and Tanzania in search of pastures.

Adult education empowers women and helps raise their standard of living, Pardiyio said. “By coming to school, they are empowered and they can run their own businesses,” he says. “They become leaders since they know how to read and write.”

They are also able to read their Bibles, and some have become evangelists in their churches. Others have become community health workers.

Pardiyio said being a teacher isn’t easy and involves following up with students facing sensitive issues. “You have to talk to their husbands for them to be allowed to come to school,” he said

Besides teaching the adults, Pardiyio is an elder in Friends International Church in Ilbissil. So far, he has trained and graduated six evangelists and six pastors from the class.

“I have a burden for people to read and write,” he said. “I just want to help them to improve their lives.”

Esther Kasani is a 50-year-old grandmother and student in Pardiyio’s class. She is married and has five children of her own. She said she came to class to learn how to read both the Bible and instructions on her medication.

She was also born into a polygamous family. “My parents did not see the need of taking girls to school,” she says. “Now I know how to read Kiswahili and I am learning how to read Kimaasai.”

She said she decided on her own to enroll for the classes, and her husband is happy with her progress. Kasani can now assist her grandchildren with their homework and said reading helps her better serve in her church.

“It has made my work easier,” she said proudly. “I can now read the Bible myself.”

She was also born into a polygamous family. “My parents did not see the need of taking girls to school,” she says. “Now I know how to read Kiswahili and I am learning how to read Kimaasai.”

She said she decided on her own to enroll for the classes, and her husband is happy with her progress. Kasani can now assist her grandchildren with their homework and said reading helps her better serve in her church.

“It has made my work easier,” she said proudly. “I can now read the Bible myself.”