By Brian Nixon

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO (ANS) — I stood in a line to see Shakespeare. Like any groupie, I was gawking, geeking, and groping to see the celebrity. But a point of clarification is in store: it wasn’t the actual Shakespeare I was gawking at—that would be weird to geek out over a 400-year old dead body, even if it were on tour from its home in Warwickshire, England. No, it was the work of Shakespeare—his first folio—that caused a thousand people—media included—to grope to see the work of the English bard.

On February 5, 2016, the opening reception for First Folio! The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare was unleashed upon the United States oldest capitol, Santa Fe. As part of a national tour, the Shakespeare folio is roving the country, on loan from the Folgers Collection.

All of this, of course, is in celebration of the anniversary of Shakespeare’s 400th death.

Good ol’ William was born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, England. He died in April 1616. The in-between stuff—his life and work—is the material of legend. His childhood is murky, little is known. He married at age eighteen to an older woman, twenty-six year old Anne Hathaway. Together they three children: a girl, Susanna, and twins, Hamnet (a boy) and Judith (a girl). Hamnet later died at age 11. What Shakespeare did for living at this time in his life is up for speculation: some claim he was a schoolteacher, others say he was honing his chops in theater, and even others claim he was criminal. Maybe he was all three. We may never know.

Good ol’ William was born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, England. He died in April 1616. The in-between stuff—his life and work—is the material of legend. His childhood is murky, little is known. He married at age eighteen to an older woman, twenty-six year old Anne Hathaway. Together they three children: a girl, Susanna, and twins, Hamnet (a boy) and Judith (a girl). Hamnet later died at age 11. What Shakespeare did for living at this time in his life is up for speculation: some claim he was a schoolteacher, others say he was honing his chops in theater, and even others claim he was criminal. Maybe he was all three. We may never know.

What we do know is that the 1590’s were an important decade in Shakespeare: he began writing. We don’t know the exact start date of his career as a writer, but most Shakespearean scholars would attest that by 1592 Shakespeare had a play in production. How do we know this? Because his work was attacked in print: another playwright, Robert Greene, wrote some bad words against the Bard, calling him an “upstart crow.” Oh, poor, Robert Greene. Little did he know!

By 1594, Shakespeare’s work started to be published. And by 1598, his work was well known. The rest is literary history. Shakespeare gave the world many gifts: 37 known plays and 154 poems—or sonnets. All of this brought him fame and money. He ended buying a fine home in Stratford.

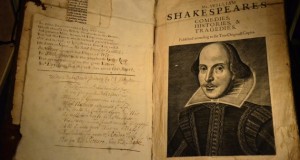

It was the first edition of these collected works that I went to see in Santa Fe. According to Cynthia Baughman—writing for the Santa Fe magazine, El Palacio, “When William Shakespeare died in 1616, eighteen of his plays, including Macbeth, The Tempest, and As You Like It, had not been published. Seven years later, in 1623, two members of his troupe collected his plays into Mr. William Shakespeare’s [sic] Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, a book now referred to as the First Folio, and one of the most important in the history of print.

“Were it not for the editing efforts of his fellow actors John Heminge and Henry Condell, many of Shakespeare’s greatest works might have been forever lost. The book’s frontispiece, an engraving by Martin Droeshout, is a now-iconic portrait of Shakespeare, which, though made posthumously, was considered an excellent likeness by people who knew him.

“Of the roughly 750 copies of the First Folio published, 233 copies survive, the largest collection of them, 82, held by the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC [1].”

To say Shakespeare’s works have had an influence upon culture is a gross understatement; they are, as stated by Baughman, “one of the most important in the history of print.” And other than the English Bible, they are part of the standard works found in the English language (Chaucer’s, Canterbury Tales, is up there as well). From movies to radio, to perpetual performances and printed works, from cartoons to caricatures, Shakespeare continues to have a lasting impact. Writers as diverse as Charles Dickens, Herman Melville, and William Faulkner have told of their allegiance to Shakespeare. And even English language itself has benefited from Shakespeare’s works: he added words and phrases such as “bated breath” and a “foregone conclusion” to our repertoire.

With all the influence Shakespeare had upon our culture, the question is: who influenced Shakespeare? The answer is hard to determine. Were there other authors? Undoubtedly. But if we look at the works themself, one point of influence is clear: the Bible.

According to scholar and professor of English, Leyland Ryken, “The most frequently repeated figure on the books of the Bible to which Shakespeare refers is 42 books—eighteen from each of the Testaments and the remaining from the Apocrypha. Shakespeare’s writing contains more references to the Bible than the plays of any other Elizabethan playwright. A conservative tally of the total number of biblical references is 1200, a figure that I think could be doubled.”

Ryken continues, “Numerically the book with the most references is the book of Psalms, and usually Shakespeare refers to this book as it appears in the Anglican Prayer Book. Other biblical books that are high in the number of references are Genesis, Matthew, and Job. The Bible story that appears most often—more than 25 times—is the story of Cain and Abel. There are so many references to the opening chapters of Genesis in Shakespeare’s plays that scholars make comments to the effect that Shakespeare must have had these chapters nearly memorized. Shakespeare’s allusions are sometimes generalized, as for example to characters in the Bible, but often the parallels are linguistic and specific, requiring a specialist’s knowledge” [2].

So if I’m reading Ryken properly—and I think everyone should read his essay—one of Shakespeare’s greatest influences was Scripture.

Ryken concludes his essay with the following: “I believe that the pervasive presence of the Bible in Shakespeare’s plays refutes two common fashions on the scholarly scene today. One is the myth that Shakespeare is a secular author. On the contrary, the biblical presence sends a signal about the intellectual allegiance of Shakespeare’s plays. Secondly, it is not simply the English Bible but the Geneva Bible, specifically, that primarily appears in Shakespeare’s plays. The claim that Shakespeare was a closet Catholic has recently received a prominence that is without warrant, and Shakespeare’s use of what was for the Catholics a forbidden book is one evidence among many that Shakespeare was Protestant in his religious orientation.”

For those not familiar with the Geneva Bible, a few words are in store about the history of the Bible in English.

The Protestant Reformation had an immense impact on the wide dispersal of the Bible in the common people’s language. After Luther translated the Bible into German, other scholars began to do the same in their native languages. In England, the work began with John Wycliffe (who, incidentally, influenced Luther’s ideas). What follows is a concise timeline of the Bible’s development:

- The Wycliffe Bible—John Wycliffe (1320–1384) utilized the Latin Vulgate (a work translated by Jerome in Bethlehem) as its base. It was translated c. 1384.

- The Tyndale Bible—William Tyndale (1494–1536) used Luther’s translation as the basis of his work. It was largely completed in 1534; two years later Tyndale was murdered because of his work on the Bible.

- The Coverdale Bible—Miles Coverdale (1488–1569) based his work on Luther’s and Tyndale’s works and the Latin Vulgate. The first edition was completed in 1535.

- The Matthew Bible—an English translation that is largely based upon the work of Tyndale and Coverdale. John Rogers, Tyndale’s friend, combined the works of both Coverdale and Tyndale to create this new translation. It was published in 1537.

- The Great Bible—a revision of the Matthew Bible. The King’s general, Thomas Cromwell, asked for a new update. The majority of Coverdale’s changes were the extraction of controversial marginal notes. It was published in 1539.

- The Geneva Bible—a work of distinctly Protestant men exiled to Geneva, Switzerland. When Protestant refugees left England under Queen Mary (“bloody Mary”), they translated the Geneva Bible from its original languages, and it was officially published in 1560. The Geneva Bible became England’s most popular Protestant Bible, and, as pointed out above by Ryken, was used by Shakespeare, Puritans, and American reformers.

- The Bishops’ Bible—encouraged by the ruling English bishops, Matthew Parker published the Bishops’ Bible as a reaction to the Geneva Bible. It had less anti-Rome overtones, and was the favored translation of the Church of England. It was published in 1568.

- Authorized Version (KJV)—first published in 1611, the King James Version was the work of fifty-four translators, broken up into three groups and two companies, whose responsibility was to provide a new translation that was to be used in all of England. The translators were some of the most godly and learned men of their day. Although the Authorized Version had a slow start, it has flourished as one of the greatest works in the English language. It was based largely upon the Textus Receptus and Byzantine Texts.

From the KJV on, a plethora of translations in English have followed, all utilizing differing Greek texts (Byzantine, Alexandrian, or a combination of both). But as noted, it was the Geneva Bible—a Protestant-influenced work—that inspired Shakespeare.

So though it is fun to geek out on Shakespeare’s work in Santa Fe, I’m geeking out even more of the profound impact the Bible has had on the best and brightest writers throughout modern history.

So do yourself a favor upon the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death—read one of his plays. But more importantly, read the book that influenced the Bard, the Bible.

If you’d like to see the book for yourself Brown University will host the Rhode Island visit of First Folio on April 11 to May 1, 2016