Q&A | Brian Ivie tells how he found Jesus through the lens of a camera in South Korea

By Warren Cole Smith

As a 21-year-old undergraduate film student at the University of Southern California (USC), Brian Ivie read an article about a Korean pastor who saved disabled babies abandoned on the streets of Seoul. Ivie, who was not then a Christian, was drawn to the story. Over the course of making what he originally thought would be a short documentary, he was moved by the pastor’s love, and that love drew him to Christ. Now a feature-length film, The Drop Box will appear on nearly 1,000 screens today for a three-day release sponsored by Focus on the Family. Ivie also wrote a new book with Ted Kluck, called The Drop Box, that was just released by David C. Cook. Ivie and I had this conversation late last year in Atlanta where Ivie and a team from Focus on the Family screened the movie for a group of Christian leaders.

As a 21-year-old undergraduate film student at the University of Southern California (USC), Brian Ivie read an article about a Korean pastor who saved disabled babies abandoned on the streets of Seoul. Ivie, who was not then a Christian, was drawn to the story. Over the course of making what he originally thought would be a short documentary, he was moved by the pastor’s love, and that love drew him to Christ. Now a feature-length film, The Drop Box will appear on nearly 1,000 screens today for a three-day release sponsored by Focus on the Family. Ivie also wrote a new book with Ted Kluck, called The Drop Box, that was just released by David C. Cook. Ivie and I had this conversation late last year in Atlanta where Ivie and a team from Focus on the Family screened the movie for a group of Christian leaders.

Tell me about The Drop Box. What’s the movie about? The Drop Box is a documentary feature film about a pastor in Korea who built a mailbox for abandoned babies where nearly 600 babies have been saved. He built this in one of the poorest districts of Seoul, the capital of South Korea, after finding a little girl with Down syndrome on his front steps during the winter time. He wanted to find a safer way for them to be surrendered, so he built this box.

How did you find out about this story? I actually read an article in the Los Angeles Times on June 20, 2011. That article was called “South Korean Pastor Tends an Unwanted Flock.” It was all about the man who built the mailbox for abandoned babies, but not only that, the babies had physical disabilities or deformities. He was saving, in some ways, the most disposable children of all.

Were you still in film school whenever you read this article? I was in film school. I was a rising junior at USC film school. … I’ll never forget reading this article. I read it in the actual, physical newspaper over my breakfast cereal. I’ll never forget reading the article and reading about the man who built the mailbox and thinking, “If I don’t do anything about this, if I don’t tell this story, everyone’s going to forget.” That’s what I thought that morning. I decided to send an email out to the correspondent in Korea, get all his contact information and get in touch with the pastor, try to make a film about his life.

What happened from that first article and that first email to that correspondent? It was never supposed to be a feature film. It was actually planned out, from the very beginning, to be a five- to 10-minute short film that we were going to make. The bent of the movie is that it was going to pit this kind of Korean society of perfectionism—because there’s a lot of plastic surgery in Korea and it’s a very perfectionistic culture —against this man’s counterculture of taking in children with deformities and disabilities. He was rebelling against what seemed to me, at the time, to be Korean society at large. What I will tell you, and kind of the interesting twist to this whole narrative, is that I became a Christian while making this film. What I didn’t expect is that when I was going to go make a film about saving Korean babies that God was going to save me.

Did working on this film lead you to Christ, or were there other factors involved here? Like Lee Strobel would say, there are a lot of links in the chain, that’s for sure, but this was the first time I felt like I had experienced true love. Love that wasn’t about being weak at the knees, but something that was gritty and something that was sacrificial. Seeing this pastor and how he had drawn a line in the sand and said, “No one dies here,” and had built, in some ways, a bunker for babies and said, “I’m going to take care of you. I’m going to go after you, even though you may never know that I’ve done this for you, even though you may never know that you needed to be rescued.” That, to me, really mirrored the love of the Father. When I saw myself as one of those children, that’s when everything changed.

Did working on this film lead you to Christ, or were there other factors involved here? Like Lee Strobel would say, there are a lot of links in the chain, that’s for sure, but this was the first time I felt like I had experienced true love. Love that wasn’t about being weak at the knees, but something that was gritty and something that was sacrificial. Seeing this pastor and how he had drawn a line in the sand and said, “No one dies here,” and had built, in some ways, a bunker for babies and said, “I’m going to take care of you. I’m going to go after you, even though you may never know that I’ve done this for you, even though you may never know that you needed to be rescued.” That, to me, really mirrored the love of the Father. When I saw myself as one of those children, that’s when everything changed.

Was that the point when this five- to 10-minute student project became something more? That’s correct. We go on the first trip in December 2011. I come back, and I really experience what it means to be fully known with all of the things that I was ashamed of and yet fully loved, meaning that God wanted me still, even knowing everything about me, even all the darkest secrets. After that, I really did go back to Korea to make an entirely different film, and that film was going to be about the Father’s heart. The goal of the movie now, as it stands as an 80-minute feature film, is to be a love letter from the Father to the world.

How did you negotiate this pivot from the short student film to an 80-minute documentary that had a decent-sized budget? We initially were planning to raise money just through Kickstarter. … We were going to post $5,000, go shoot the movie on whatever crappy cameras we could get our hands on. At the last minute, I decided instead of posting $5,000, I was going to post a $20,000 goal, and we reached that goal very quickly. The day after that, I got a phone call from somebody who said, “I’d like to match your goal,” so we had $40,000. I asked him why, and he said, “You’ll understand later,” and I really did. Then I got another phone call.

It was not an anonymous person? It was not, but they’d like to remain so. This is what kept happening. Again, I wasn’t a Christian at the time. I was seeing these people come out of the woodwork. For me, Christians, at the time—well, evangelical Christians—were crazy people, hypocrites, haters, whatever you want to call them, but I was experiencing something really authentic. People were giving in a very authentic fashion and did not want to be known for it, and then it happened again. We had another $25,000 donation that came and said, “I want this story to be told, please. Here’s the resources to do it.” So we had $65,000 to make our short film. Already, even in 2011, we’re thinking, “This could be a lot bigger.” On top of that, a Korean girl from USC came up to me one day and said, “You should give a friend of my mom a call.” At this point, all these phone calls could mean is thousands of dollars.

I give this woman a call and she basically says, “Hi, I read the same article as you. What can I do? Can I charter a plane? Is there anything I could do for you?” I said, “You know what Laura? That’s already taken care of, but I know that your husband is the president of Oakley Optics, and I know that Oakley Optics co-founded a company called RED Camera, and Peter Jackson’s shooting The Hobbit on the RED camera right now. Would you buy me a RED camera to make this movie?” And she said, “Of course I will.” I walked into RED headquarters, walked out with $50,000 worth of camera equipment as Peter Jackson was shooting The Hobbit in New Zealand, and we went to Korea with the same equipment. It was these miracles. I was starting to think, “Man, there’s something to this God guy.”

You were seeing amazing things done. I got to see God work in those ways and, of course, it’s grace. I wasn’t even a Christian. People who were donating, who knows if they knew I was a Christian, but they knew the character of the man that I was making the movie about, and I did not yet. We had $65,000 [cash], $50,000 in camera equipment, and we flew 11 people to Seoul on Dec. 15, 2011, to make a documentary on the man who built a mailbox for abandoned babies.

Upon coming back from that first trip, where we had spent a significant amount of money, … we had enough footage to make a full-on movie, but what I realized was that we had made the movie I wanted to make. I felt like there was another movie that we needed to make after I got saved. That movie was much more about the Father’s heart.

The way we shot the second trip to Korea was we didn’t go for people with titles. We didn’t go to experts. We just stayed in that little home where that pastor was and talked to his children and talked to him and the staff. That’s the majority of the film, ordinary people doing extraordinary things with the love of God, motivated by it and relying on it. It was the foolish shaming the wise, and the same with us, the motley-crew that we were, having never worked on these cameras before. I was watching YouTube videos to figure out half of the things we needed to accomplish. It’s an amazing opportunity when I get to talk about it, to say, “It was God.”

What made you decide to hook up with Focus on the Family? What’s the outcome of this partnership from your point of view? I think the goal for me is unification. I think it’s very easy for young Christians to get very jaded about what that previous generation is doing with storytelling. The normal perspective from a believer in my neck of the woods, in Los Angeles, is, “Eck, the Christians are making faith films. They’re so corny. They don’t really get to the authentic parts of the issues.” What I’ve seen is a need for a unity from generation to generation. What’s amazing about our partnership is the marriage of our youth and energy and their wisdom and their experience and their resources, and it’s the same spirit.

What are you doing to grow in your personal faith as a new, young Christian? The biggest thing is allowing myself to be adopted by people who have been walking with Him for a long time, meaning, that I have spiritual parents. … They speak into my life. They speak into my relationship with my girlfriend now, who is soon to be more than a girlfriend. … I also, weekly, have prayer calls with a really amazing man of God , just to stay current in the things that I’m dealing with. … On top of that, of course, I’m in an amazing community. I go to a great home church called Reality LA, where I know people are trophies of grace that lead that church. Our pastor was an ex-meth addict. Now he leads a flock of thousands of people. It’s the real deal. I have church, my community group and [I’m] surrounded by people, but more than anything, it’s about experiencing the Father loving me, even right now. That’s my greatest accountability. It’s staying intimate with Him because Christianity isn’t something that you know or something you do. It’s something you become. For me, as I become more like Him, then I’ll start saying those things. It’s just part of who I am now.

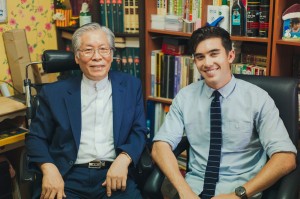

Caption1 – Pastor Jong-rak Lee with Brian Ivie

Caption2: A depository—literally, an oversized metal mail box—sits outside Lee’s Presbyterian Church in South Korea’s capital. It is lined with a blanket and equipped with heating to keep abandoned babies safe from the cold.